Movie Copyright Litigation from 1915: O’Neill v. General Film Co.

Today’s New York Times ran an article about the modernization of the Archives for New York County, and it reminded me of some research I did there for my draft article on common-law copyright. Although I ended up not using it that much, I tracked down the files from a number of nonmusical common-law copyright cases, and this led me to the same New York County Municipal Archives, to look at the case file for O’Neill v. General Film Co., 171 App. Div. 854 (N.Y. App. Div. 1916).

The case was brought by James O’Neill, best known today as father of Eugene O’Neill, but an important actor of his day who owned the American common-law copyright rights to Charles Fechter’s English stage adaptation of the County of Monte Cristo. He sued the General Film Company for distributing a film also based on the novel The Count of Monte Christo, which he alleged was also based on Fechter’s adaptation, and made substantially the same editorial and dramatic choices as Fechter. 1 O’Neill had been playing the lead role of Edmond Dantes for some 35 years by this point, to tremendous financial success, and in the same year the suit was originally brought (1912), he had starred in an authorized adaptation of The Count of Monte Christo.

Both sides hired prominent lawyers. The plaintiff hired Dittenhoefer, Gerber & James, likely the leading theatrical law firm of its day – Judge A.J. Dittenhoefer had been a leading theater lawyer for decades at this point.2. The defendant hired Nathan Burkan, a rising star in the legal world who only a few years later (and before the appeal was decided) would help found ASCAP.

At trial, the Court took testimony and ruled in favor of the plaintiff O’Neill, holding that the motion picture at issue infringed his rights in the the Fechter play at common law. On appeal, the Court had no difficulty affirming the trial court on the count of copying, but found the question of chain of title and publication more pressing. On the question of whether O’Neill truly had valid title to the common-law rights in the play the Court was equivocal, finding the evidence scanty, but ultimately affirmed the trial Court and held that he had produced sufficient evidence to bring the case and create a rebuttal presumption of ownership. The Court had the most difficulty with publication – they agreed that performance of the play or taking photos of the production did not constitute a divestative publication that would destroy common-law rights, which only made sense following existing NY precedents and the US Supreme Court’s recent decision in Ferris v. Frohman. However, O’Neill had signed a contract several weeks earlier with the Famous Players Film Co,3 and the Court was concerned that this might have been a divstative publication of the unpublished play. In the end, the Appellate Division held that the motion picture rights to any part of the unpublished play that were used in the authorized motion picture were deemed published, and thus the common-law rights had been lost. However, O’Neill retained the common-law film rights to whatever parts of Fechter’s play had not been used in the motion picture.

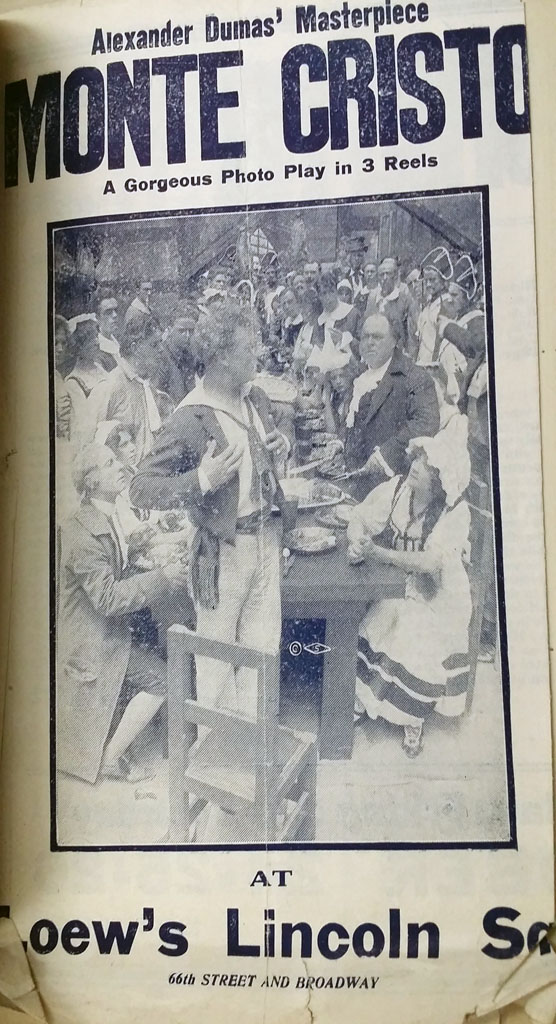

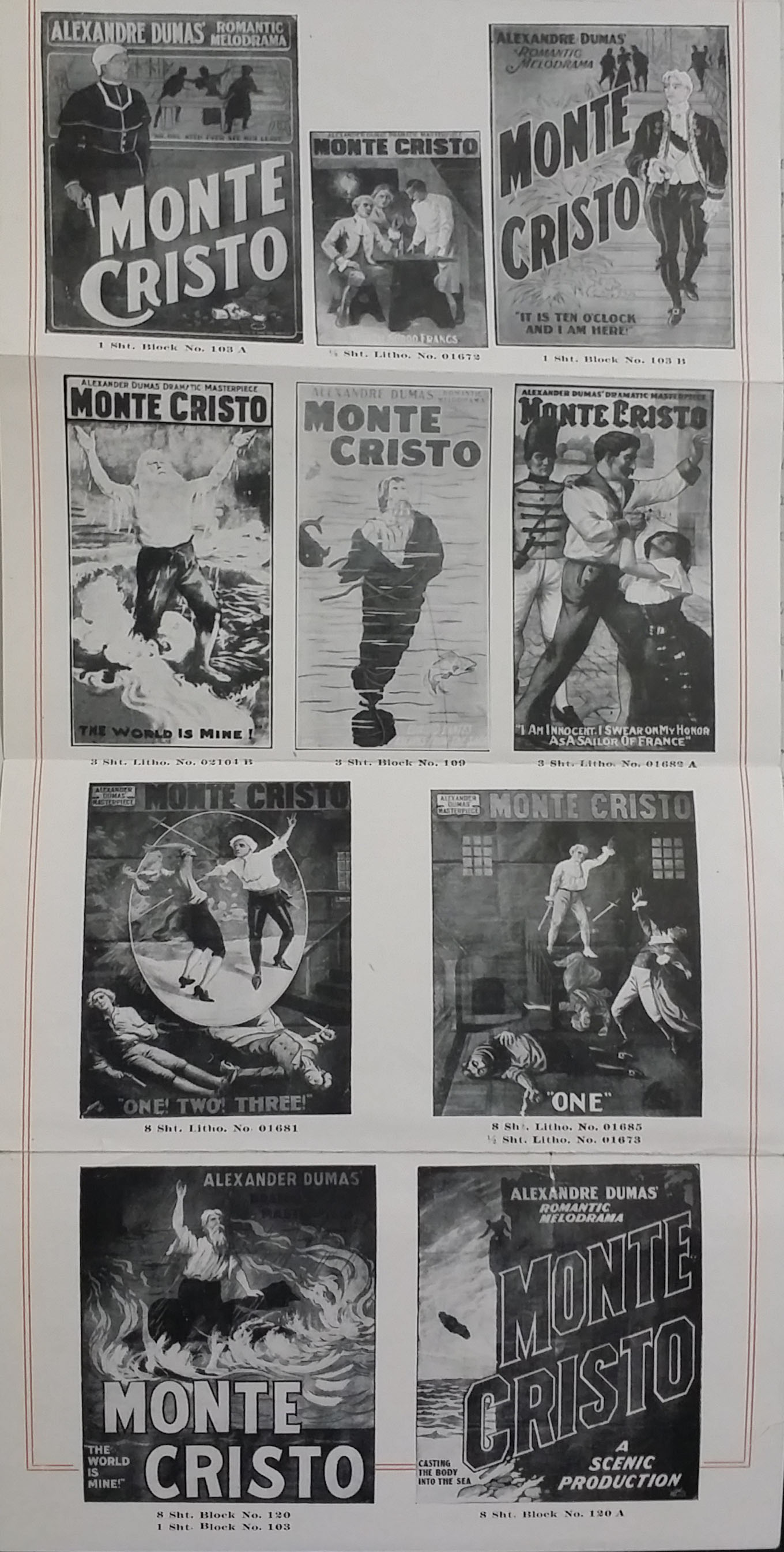

The printed record of the case on appeal, which I scanned at The New York State Library in Albany, proved much more manageable than the original handwritten records of the case at The New York County Archives. It contains a transcript of the testimony at trial which includes extensive documentation of theater practices for common-law copyright, by the plaintiff and others.4 The appellate briefs of the parties are also included, laying out the issue of common-law copyright as it was understood as of 1915. However, not everything from the records in the New York County Archives is reproduced in the printed appellate record. Notably, the New York County Archives has what appears to be a complete copy of Fechter’s dramatization, dated 1868. Fechter’s drama has been reprinted several times, although not recently, and in differing versions. It might be of interest to literary scholars. In addition, the case file included a number of advertisements as exhibits; I’ve included them after the jump.

- The film was not actually made by General Film, but rather by the Selig Polyscope Company in Chicago. General Film was the distribution company of the Edison Trust. ↩

- Dittenhoefer is best-remembered today for his association with Abraham Lincoln ↩

- Famous Players later merged into what would become Paramount ↩

- The testimony begins at page 61 ↩