23

Aug

2017

Performance Rights at Common Law in 1880s San Francisco

As I’ve mentioned a few times on this blog, and will mention many more times, I currently have an article going through the editing process at the University of Cincinnati Law Review, which attempts to be a systematic study of common-law copyright, both generally and as applied to sound recordings, with a specific focus on performance rights. This is part of a series of posts where I focus on specific cases/examples from that paper, and share some of the primary source documents.

In this post I will discuss two suits against the owners of the Tivoli Opera House in San Francisco for infringement of their common-law copyright by performing unpublished light opera (aka operetta) without a license. The cases are from the mid-1880s, which might seem like deep esoterica, but in fact I think they offer unique insight into the contemporary common-law copyright cases currently ongoing, in this case specifically the Flo & Eddie v. Pandora case currently being briefed before the California Supreme Court. This is because, as I’ll explain more below, the 1880s and early 1890s offer a unique window into the question of whether a performance right exists at common law. This is because federal law did not include performance rights for music at the time, but courts essentially universally found that common law copyright, which only protects unpublished works, did offer an exclusive performance right. As a result, (a) questions of common-law copyright and its scope became especially important at this time, and (b) it strongly suggests that common-law copyright does not obey the limitations on performance rights that federal law does.

As the WPA Guide to San Francisco explains,

No American Theater did so much to popularize opera as the Tivoli, best remembered of all of San Francisco’s theaters, which Joe Kreling opened as a Beer Garden in 1875, with a 10-piece Orchestra and Tyrolean singers. Rebuilt in 1879, it became the Tivoli Opera House. Its career began happily with Gilbert & Sullivan’s Pinafore, which ran for 84 nights. For 26 years thereafter it gave 12 months of Opera each year, never closing its doors, except when it was being rebuilt in 1904: a record in the history of American Theater. For eight months of the year light opera – Gilbert and Sullivan, Offenbach, Van Suppe, Lecoq- was performed, and for 4 months, grand opera, principally French and Italian occasionally Wagner. From the Tivoli chorus rose Alice Nielsen, the celebrated prima donna.

Unmentioned in this excerpt is whether the Tivoli had the rights to perform any of these works. The situation of performance rights as of the 1880s was a particularly complicated one under the federal statute. There was a performance right for drama under a 1856 Act, codified into the 1870 revision of the copyright law, but it did not expressly include music (music had been added to the copyright act in 1831, but that act included no performance rights whatsoever). The question of whether the act creating a performance right for dramatic works included music remained open until 1885, when the Circuit Court in New York conclusively rejected such an argument in The Mikado Case, about the Gilbert & Sullivan operetta.

In truth, though, whether or not the federal act included a performance right for music mattered little, since almost all composers were based out of Europe, not the United States, and foreigners were not protected by federal law at all until 1891 anyway (Gilbert & Sullivan had concocted an extensive scheme to get an American copyright, which I discuss much more in an article). Accordingly, given that federal law did not protect them – both because they would not have a performance right, and because even if they did, they could not get an American copyright, European opera composers hoping for recompense for their labor in the American market were forced to rely on common-law copyright.

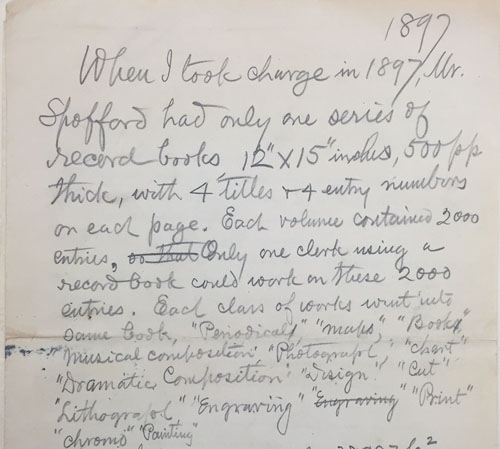

Into this gap stepped Leo Goldmark, who in the 1880s took on a role somewhat similar to that which Flo & Eddie have taken on in this decade – advocating for performance rights at common law. Leo Goldmark is mostly best known today for his family members than his own legacy,1 but his own career was focused on the law, which he took up in the 1870s after emigrating to America. Around 1880, with both musical training himself and connections to major composers, Goldmark began a national campaign of bringing lawsuits against various opera companies, accusing them of infringing the common-law rights of the unpublished parts of operettas.

The unpublished aspect was always a bit complicated, since for most of these operas the actual songs had been published in piano/songbook reduction. However, Goldmark premised his arguments on the unpublished parts of the opera – the unsung dialogue, the stage direction/choreography, and the orchestration. Courts across the country showed no resistance to this argument, liberally handing out injunctions. By the time Leo Goldmark brought suit against the Krelings in September of 1885, the case file reveals that he had already filed 26 other such lawsuits all across the country. In this case he accused them of performing the operetta Nanon by Richard Genée without permission of the American rightsholders.

The US Circuit Court in San Francisco (the Circuit Court was a trial court until the 1890s) quickly found that Goldmark had a right to an injunction against performance of the operetta at common law. The Court did not treat the matter lightly though, and indeed the presiding judge had initially denied the application for an injunction, but on a petition for rehearing invited the other federal judges from California to sit with him, and at that rehearing reversed his initial opinion and granted the injunction.

The matter continued to fester for a number of years, and in 1888 the Court,2 found that Nanon was protected by common law in the United States, because even assuming a authorized publication had occurred of some of the songs from the show, because other aspects of the operetta like the orchestration and interstitial dialogue had not been published. The Court thus enjoined the Krelings from performing any part of Nanon that had not been published, but held that they could use their orchestration of the music for the opera, which they had created independently from the published piano score, and not copied from the unpublished original orchestration

The issue of orchestration and publication would be explored more in a second case brought against the Krelings by Thomas Henry French, manager of American operations for the theatrical licensing company (to this day) named after his father, Samuel French. The lawsuit was commenced in early 1886 and was likely inspired by Goldmark’s similar suit, and the Courts in San Francisco seemed to treat it as being of a piece with the Goldmark suit, enjoining the Tivoli from performing the operetta Falka due to French’s common-law rights in the opera.

This litigation would run for many years, until the Circuit Court in 1894 decisively ruled that although a book of the songs from the original French version of the opera had been published, the complete orchestration and other aspects of the operetta had not been published, and had been infringed under common law. Critical to that finding was one of the unpublished manuscript scores being found as part of the discovery process, and in turn included in the case file.

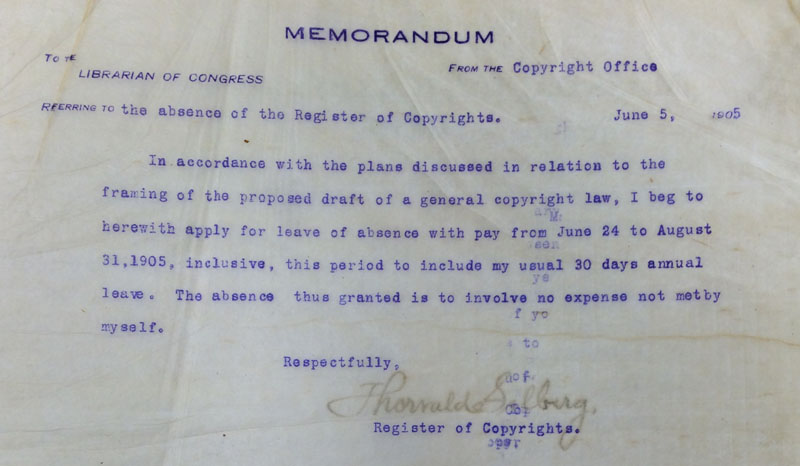

The decisions themselves are important reading for those seeking to understand common law copyright in California. The case files, which I scanned from the National Archives Regional Division near San Francisco, are likewise fascinating. For instance, the case file for French v. Kreling includes the transcript of a testimony of the in-house orchestrator of the Tivoli opera house, where he goes into great length about the then-common practice of having an individual such as himself on staff, tasked with orchestrating published piano scores into orchestral scores, to avoid paying royalties due to common law. There are also copies of many of the opera libretti at issue in these cases included in the case files – I didn’t scan the entire volumes, but included scans of the cover pages should they be of interest to musical historians.

At least in the 1880s, it was pretty clear that California common law included performance rights for musical compositions, regardless of whether federal law did, a situation somewhat analagous to the situation today for terrestrial radio.. As the question of whether the codification of California common law includes a performance right is currently before the California Supreme Court, this seems like an important time to analyze.3

- His brother Carl Goldmark was a major composer at the time, best known today for his violin concerto and other orchestral pieces, but best known at the time for his opera The Queen of Sheba. Leo Goldmark’s son Rubin Goldmark was himself a major composer during his life, although his compositions are mostly forgotten now and he is best remembered for teaching Aaron Copland and George Gershwin. ↩

- in the interim California had been split into two Districts, with the court in San Francisco becoming the Northern District ↩

- Of course, the California Supreme Court is looking specifically at digital services that are required to pay performance royalties through SoundExchange, in this case Pandora, but the cases brought by ABS and others arguing that there is a performance right for terrestrial radio loom in the background. ↩